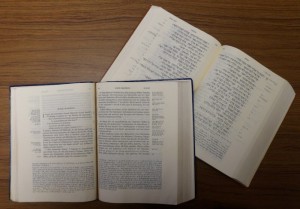

To better lead Christ’s flock, Lutheran pastors are trained to read the original languages of the Bible, illustrated here with the 27th edition of the Nestle-Aland Greek New Testament and the 1990 edition of the Stuttgart Hebrew Bible (Old Testament).

When we say that Pilgrim Lutheran Church is where Biblical and confessional Lutheran Christians gather to receive the forgiveness of sins, a lot is packed into the modifiers “Biblical” and “confessional”. In short, what we believe is solidly based on the Bible and expressed by the Lutheran Confessions. The following further unpacks those words.

- When we call ourselves “Biblical” we mean that we believe that the Bible is the inspired Word of God and is therefore inerrant (without error) and has continuing authority for our lives today. We interpret the Bible literally, according to its different types of writings, which in some cases includes figurative language. The Bible gives the “form” to the faith, but Jesus is the “material” or content, and faith in Him precedes belief in the Bible itself. Holy Scripture is understood both as law, which shows us our sin, and as Gospel, which tells us what God has done about our sin. The Bible clearly reveals the Christian faith, so that faith can be grasped, understood, and, therefore, accurately stated, taught, and confessed, as has been done in confessional Lutheranism.

- When we call ourselves “confessional” we mean that we subscribe to the Lutheran Confessions (documents contained in The Book of Concord of 1580) because (in Latin quia, not quatenus, “in so far as”) they correctly confess the teachings of the Bible. These Confessions are based on the Bible and with the Bible are the basis of what we believe, teach, and confess—in word and deed. We do not pick and choose what to believe.

People being confirmed into the Christian faith at Lutheran congregations are usually asked something along the lines of this question:

Do you hold all the prophetic and apostolic Scriptures to be the inspired Word of God and the doctrine of the Evangelical Lutheran Church, drawn from them and confessed in the Small Catechism, to be faithful and true? (Lutheran Service Book: Agenda, 32)

The given answer to that question is “I do.” Lutherans and their congregations are thus properly said to be Biblical and Confessional. (The Bible’s authority is, of course, the greater.)

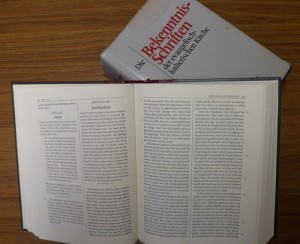

The Lutheran confession of faith is illustrated here with the second edition of Concordia: The Lutheran Confessions, an accessible English version of the documents, and the 12th edition the critical edition of the documents in their original German and Latin languages.

Martin Luther’s Small Catechism (distinguished from but included with the LCMS “Short Explanation” of the Catechism in the little blue, now burgundy, books many know) is surely the best-known exposition of “the doctrine of the Evangelical Lutheran Church”. Luther’s Large Catechism is probably also among the better known of the Lutheran Confessions.

When you hear or read someone refer to the Lutheran Confessions, any or all of the following might be meant.

-

- Apostles (or Apostolic) Creed, dated around the 2nd century, author unknown. Authoritative in Greek and broken down into 3 articles.

-

- Nicene Creed, 325 and modified in 381, adapted by church leaders assuembled in Niceea and Constantinople. Authoritative in Greek and broken down into 3 articles.

-

- Athanasian Creed, emerged between the 6th and 8th centuries, named for Athanasius but not authored by him. Authoritative in Latin and arguably in two sections.

-

- Small Catechism, 1529, written by Luther, intended for teaching lay people the basics of the faith. Authoritative in German, usually thought of as divided into six parts, and usually abbreviated SC.

-

- Large Catechism, 1529, written by Luther, for pastors and teachers. Authoritative in German, divided into five parts (though arguably the same six as the Small Catechism), and usually abbreviated LC.

-

- Augsburg Confession, 1530, written by Luther’s colleague in Wittenberg, Philip Melanchthon, for presenting to the emperor at a Diet (a meeting of the government) in Augsburg as a statement of the faith’s chief articles and abuses corrected by the Lutherans. Authoritative in German and Latin, organized into 28 articles, and usually abbreviated AC.

-

- Apology of the Augsburg Confession, 1531, by Melanchthon as the defense of the Augsburg Confession in answer to the Roman Catholic church’s reply to the Augsburg Confession, the Roman Catholic Confutation. Authoritative in Latin, organized after the same 28 articles, and abbreviated Ap.

-

- Smalcald Articles, 1536, by Luther, intended for a church council that was never held. Authoritative in German, divided into three parts (1 article in the first, 4 articles in the second, and 15 in the third), and usually abbreviated SA (though in the material we are using in the special Bible class series this work is at least once abbreviated SC).

-

- Treatise on the Power and Primacy of the Pope, 1537, by Melanchthon, adopted as an appendix of sorts to the Augsburg Confession. Authoritative in Latin, written in five unnumbered sections, and usually abbreviated Tr.

-

- Formula of Concord, 1577, by men such as Jacob Andreae and Martin Chemnitz, further expounds the Augsburg Confession, particularly on issues that were dividing the Lutherans. The Epitome of the Formula is an abridged version for congregations to study, and the Solid Declaration is the unabridged version. Each is authoritative in German, organized into 12 articles (plus a “Rule and Norm” section), and usually abbreviated Ep and SD, respectively.

All of these confessions or statements of the faith in 1580 were collected into The Book of Concord and, over the next two years or so, were subscribed to by three electors, 20 dukes and princes, 24 counts, 4 barons, 35 cities, and 8,000 pastors and teachers.

Since then, countless others have subscribed to these Confessions, including our Pilgrim congregation (see Article III of its constitution) and her pastor, at both his ordination and installation. He promised then and promises now to perform his duties in accordance with the Confessions and to conform his teaching and administration of the Sacraments with Scripture and the Confessions.

There are various editions of The Book of Concord. For example, there is a critical scholarly edition with the Confessions in their authoritative languages, called Die Bekenntnisschriften der evangelisch-lutherischen Kirche, 12th edition in 1998. There was an edition put out in 1921 by the Missouri Synod, called the Triglotta, in German, Latin, and English. A newer English translation came out in 1959 edited by Theodore G. Tappert (generally called the Tappert edition). The newest English edition,Concordia: The Lutheran Confessions: A Reader’s Edition of The Book of Concord – 2nd Edition (a revision of the Triglotta’s translation), came out from the LCMS’s Concordia Publishing House in 2007 and is targeted at those who are otherwise less familiar with the Lutheran Confessions (available from CPH here).

Note that most of the Confessions are referred to by article and paragraph number, which paragraph numbers were not original but were added later to help refer to specific passages. Sometimes “f” and “ff” are used in references to the Confessions and Bible verses, meaning the paragraph(s) or verse(s) immediately following. Sometimes “cf” and “cp” are also used in Confession and Bible references, meaning, depending on the author making the references, confer (in the sense of “see also”) and compare (in the sense of “contrast”).

We encourage members to become familiar with these confessions of the faith, for since they correctly put forth the teachings of the Bible, genuine Christians cannot disagree with them. They are encouraged to have their own copy, but anyone can find them on-line.